Following the Thread

Handcrafts and digital technology in the work of Kate Pemberton

Text by Matt Price

One of the defining characteristics of the 20th Century was the development of electronics and computer technology, bringing with it a whole material culture of circuit boards and chips, cables and adaptors, resistors and LEDs. Such new products have emerged in tandem with progress in production processes and materials, from miniature plastic microprocessors to highly effective semiconductors such as Silicon. They have not only transformed our physical world, but also innumerable aspects of our professional and private lives, from business practices and leisure time to research methods and language usage. The electronic and non-electronic worlds become further separated and yet more interwoven every day, and it is in this paradox that the practice of Birmingham-based artist Kate Pemberton is located.

By means of handcrafted artworks using traditional materials such as embroidery silk and wool, Pemberton questions life lived through a cursor, examining contemporary society's perspective on the world as filtered through a monitor.

Hide Text > That we are viewers of the world, engaged remotely through an electronic interface, is suggested by the Cursor series - hand-stitched pieces in which a jagged black arrow sits against a light blue rectangular background. This labour intensive depiction of a blank computer screen awaiting instructions offers both a poetic image of the dehumanised interaction redolent of the computer age and a poignant nod to the blank canvas of minimalist art history.

In the Pink Samplers series, computer hardware and consumables such as hard drives and DVDs are carefully stitched onto pink backgrounds. The rectangular units in which the fabric is woven correspond knowingly to the pixels that make up images on a computer screen. Perhaps some traditional approaches to image making, such as sewing, weaving and mosaics are not so far removed from digital techniques as they may appear - the grid, geometry, line and colour are shared attributes and hand-eye coordination a common denominator. That electronic sewing machines are increasingly based on digital technology brings the stitched unit and the computer pixel ever closer, and the fact that one can download digital patterns and pattern Podcasts via iTunes suggests that traditional crafts and cutting edge technology are far from mutually exclusive and to a certain extent may even be symbiotic.

That pattern making and design are meeting points of the handcrafted and the digital is further demonstrated by the artist in the Pixel Samplers series, in which computer paraphernalia such as the bomb icons that appear when a system crashes, network servers and multi-pronged sockets are transformed into cross-stitch patterns that only reveal their component parts on closer inspection. The cloned motifs that make up the patterns in these works are analogous to the repetition, duplication, loops, samples, burning and cut and paste functions characteristic of PC technology today - indeed, the titles of Pemberton's works reference the fact that many of these terms apply to both handcrafts and computing.

The relationships between function and decoration, the industrially manufactured and handmade and tradition and progress are pursued in Pemberton's series of Mouse Mats, in which the artist makes small sections of carpet with the motif of a computer mouse hand tufted into each one. Transforming the mouse mat into a literal, fabric mat in this way is a playful engagement with both semantics and semiotics - the artwork taking the concept that made the terminology originally chosen by the computer industry so apt and re-contextualising it back in the realm of pre-computer objecthood as carpet. That Pemberton's mat depicts a computer mouse makes the circle complete - while the piece of carpet could have been made at any point in the last thousand years, the electronic mouse represented on the mat specifically dates the work of art to the turn of the millennium. It is a simple yet clever work, full of reversals of meaning.

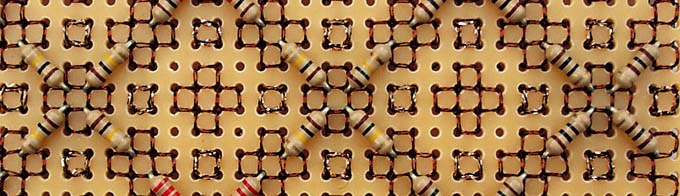

While Pemberton uses fabrics to represent the digital world, in the Electronic Embroidery series she also inverts the process, making patterns from electrical components - resistors and metallic thread are configured in decorative ways, their electronic functions laid to one side for the purposes of creating works of art. The resemblance between the electronic strip board into which the computer components are inserted and Aïda, the fabric commonly used for embroidery, is striking - the combination of rows of perforations and interconnecting strands turning the utilitarian into the purely aesthetic. The comparison raises many interesting lines of enquiry in relation to Pemberton's work, such as the history of machinery and the significance of electricity to this history, the development of the fabrics, textile and fashion industries and the impact of electricity and electronics on them, the role of the individual in production processes and that of the division of labour, and of the value of the unique versus the mass-produced.

These ideas about originality and duplication, the handmade and the machine-made, the unique and the mass-produced are investigated in Pemberton's practice by means of Endfile, a shop in which the artist sells products that she has made, including cheap plastic novelty items revolving around iconography from the digital age. The shop is itself an art project that is both a fully functioning business and a critique of such bijou Capitalism, ironically challenging the very consumer society she is selling to. While some of her customers are unaware of this inherent critique, others are attracted to it for that very reason, purchasing kitsch products with a gentle sense of gleeful hypocrisy. The shop is, naturally, an online store, but has also appeared in the non-virtual world, commissioned by Selfridges as a temporary in-store booth in the remarkable Future Systems-designed premises in Birmingham's Bull Ring shopping centre, and also in the gallery spaces of Birmingham's leading media arts organisation, Vivid.

That Pemberton is interested in the social, cultural, political and economic aspects of the digital era as much as its physical manifestations is made equally clear in her series of Kneelers - padded mats on which Christians traditionally place their knees when praying in churches or whilst taking communion. Such kneelers regularly have patterns on them, and have often been decorated by members of the church throughout history, especially by women. Gender politics were certainly among Pemberton's thoughts when conceiving and creating her series of kneelers, raising questions about women's roles within the church, the ordination of women, and patriarchal power structures in relation to belief. It is at this point that one realises that much of Pemberton's practice can be read from the perspective of feminist critique, and that handcrafts such as sewing, knitting and crochet have as much to tell us about society as they are leisure-time pursuits, and can be as politically charged and culturally significant as any other art form.

The artist also had another agenda in mind when creating her kneelers, as rather than depicting Christian themes or motifs, they feature imagery from popular computer games, including Super Mario, Sonic the Hedgehog and Zelda. Entitled ‘The High Church of Gaming,' the series proposes that there is an analogy between the devotion and zeal of digital gaming and practising a religious faith. The digital entertainment industry of late Capitalist society is a cult with so many followers and so much money circulating within it that it undoubtedly rivals the power and wealth of the church today. Kate Pemberton's sewing box is not just a place to keep pretty cotton reels...

Matt Price is a writer and editor based in Birmingham and London

A version of this article appears in the September 2007 issue of Fused Magazine

In the Pink Samplers series, computer hardware and consumables such as hard drives and DVDs are carefully stitched onto pink backgrounds. The rectangular units in which the fabric is woven correspond knowingly to the pixels that make up images on a computer screen. Perhaps some traditional approaches to image making, such as sewing, weaving and mosaics are not so far removed from digital techniques as they may appear - the grid, geometry, line and colour are shared attributes and hand-eye coordination a common denominator. That electronic sewing machines are increasingly based on digital technology brings the stitched unit and the computer pixel ever closer, and the fact that one can download digital patterns and pattern Podcasts via iTunes suggests that traditional crafts and cutting edge technology are far from mutually exclusive and to a certain extent may even be symbiotic.

That pattern making and design are meeting points of the handcrafted and the digital is further demonstrated by the artist in the Pixel Samplers series, in which computer paraphernalia such as the bomb icons that appear when a system crashes, network servers and multi-pronged sockets are transformed into cross-stitch patterns that only reveal their component parts on closer inspection. The cloned motifs that make up the patterns in these works are analogous to the repetition, duplication, loops, samples, burning and cut and paste functions characteristic of PC technology today - indeed, the titles of Pemberton's works reference the fact that many of these terms apply to both handcrafts and computing.

The relationships between function and decoration, the industrially manufactured and handmade and tradition and progress are pursued in Pemberton's series of Mouse Mats, in which the artist makes small sections of carpet with the motif of a computer mouse hand tufted into each one. Transforming the mouse mat into a literal, fabric mat in this way is a playful engagement with both semantics and semiotics - the artwork taking the concept that made the terminology originally chosen by the computer industry so apt and re-contextualising it back in the realm of pre-computer objecthood as carpet. That Pemberton's mat depicts a computer mouse makes the circle complete - while the piece of carpet could have been made at any point in the last thousand years, the electronic mouse represented on the mat specifically dates the work of art to the turn of the millennium. It is a simple yet clever work, full of reversals of meaning.

While Pemberton uses fabrics to represent the digital world, in the Electronic Embroidery series she also inverts the process, making patterns from electrical components - resistors and metallic thread are configured in decorative ways, their electronic functions laid to one side for the purposes of creating works of art. The resemblance between the electronic strip board into which the computer components are inserted and Aïda, the fabric commonly used for embroidery, is striking - the combination of rows of perforations and interconnecting strands turning the utilitarian into the purely aesthetic. The comparison raises many interesting lines of enquiry in relation to Pemberton's work, such as the history of machinery and the significance of electricity to this history, the development of the fabrics, textile and fashion industries and the impact of electricity and electronics on them, the role of the individual in production processes and that of the division of labour, and of the value of the unique versus the mass-produced.

These ideas about originality and duplication, the handmade and the machine-made, the unique and the mass-produced are investigated in Pemberton's practice by means of Endfile, a shop in which the artist sells products that she has made, including cheap plastic novelty items revolving around iconography from the digital age. The shop is itself an art project that is both a fully functioning business and a critique of such bijou Capitalism, ironically challenging the very consumer society she is selling to. While some of her customers are unaware of this inherent critique, others are attracted to it for that very reason, purchasing kitsch products with a gentle sense of gleeful hypocrisy. The shop is, naturally, an online store, but has also appeared in the non-virtual world, commissioned by Selfridges as a temporary in-store booth in the remarkable Future Systems-designed premises in Birmingham's Bull Ring shopping centre, and also in the gallery spaces of Birmingham's leading media arts organisation, Vivid.

That Pemberton is interested in the social, cultural, political and economic aspects of the digital era as much as its physical manifestations is made equally clear in her series of Kneelers - padded mats on which Christians traditionally place their knees when praying in churches or whilst taking communion. Such kneelers regularly have patterns on them, and have often been decorated by members of the church throughout history, especially by women. Gender politics were certainly among Pemberton's thoughts when conceiving and creating her series of kneelers, raising questions about women's roles within the church, the ordination of women, and patriarchal power structures in relation to belief. It is at this point that one realises that much of Pemberton's practice can be read from the perspective of feminist critique, and that handcrafts such as sewing, knitting and crochet have as much to tell us about society as they are leisure-time pursuits, and can be as politically charged and culturally significant as any other art form.

The artist also had another agenda in mind when creating her kneelers, as rather than depicting Christian themes or motifs, they feature imagery from popular computer games, including Super Mario, Sonic the Hedgehog and Zelda. Entitled ‘The High Church of Gaming,' the series proposes that there is an analogy between the devotion and zeal of digital gaming and practising a religious faith. The digital entertainment industry of late Capitalist society is a cult with so many followers and so much money circulating within it that it undoubtedly rivals the power and wealth of the church today. Kate Pemberton's sewing box is not just a place to keep pretty cotton reels...

Matt Price is a writer and editor based in Birmingham and London

A version of this article appears in the September 2007 issue of Fused Magazine